By Art Stricklin and Eli Jordan

The 100-year history of the Dallas Athletic Club includes three different locations, three generational head pros, two championship golf courses, one legendary major championship winner and decades of memories. Back in May, the club held one of several events planned to celebrate 100 years as part of the Dallas community. However, this event would be different from most, as a true legend of the game would be in attendance. The great Mr. Jack Nicklaus was returning to the site of his PGA Championship win in 1963.

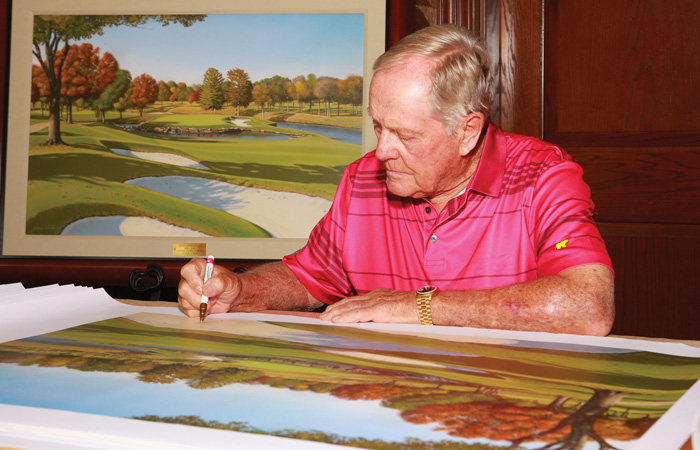

Anytime Jack makes an appearance, it’s big news and as expected, members of the club and members of the media swarmed to the property to see a once in a lifetime golf talent walk the course he so fondly remembers and listen intently as “The Golden Bear” poured over his memories of the ’63 PGA and the redesign of the club he was tasked with spearheading in the mid-80’s.

The Northeast Dallas private club began in 1919 as a premier downtown Dallas dining and workout facility. In the decades which followed it has moved to two other locations, including where it now sits on 340 acres of prime real estate in Northeast Dallas, which was once cattle land, and now hosted generations of friends, families, members and their guests.

It’s hosted the 1963 PGA Championship, the first of five such major championships won by Jack Nicklaus, who designed both the Blue and Gold courses at DAC. It was the home of caddy turned Dallas golf legend Lee Trevino, plus a bevy of championship golf, including the 1997 U.S. Mid-Amateur Championship, as well as great tennis, numerous celebrities and a century’s worth of memories.

“For the 100th anniversary of this remarkable place, we designed a wide variety of memorable events to celebrate this milestone event,” said General Manager Brent Burkhart. “We looked for ways to commemorate this huge event and we’re happy to do it each and every month.”

One early fixture of the new club, at its Glen Lakes location was Graham Ross’ position as the head golf coach at SMU, establishing the club’s long held connection with the Mustangs golf team which still continues today.

Among the assistants he brought in to help coach the SMU golf team was George Hannon who later became the head coach at the University of Texas. While at UT, Hannon coached a pair of pretty fair college golfers himself, Ben Crenshaw and Tom Kite.

Other assistants included Gene Shields who went on to be the head pro at Preston Trail Golf Club before going to Ridgewood in Waco and serving as head golf coach at Baylor University. Jerry Andrews also joined the staff and served with Ross Collins as one of Ross’ top assistants.

Among the golfers Ross helped coach at SMU were former members Jimmy and Buster Brown and briefly Don January, who grew up in Dallas and whose dad, A.C., was a member of Glen Lakes and DAC.

While the course moved to its current location in Northeast Dallas in 1954 with a layout originally designed by architect Ralph Plummer, one thing head pro Ross was not eager to change was the caddie system which he considered essential to a well-working club.

When the new location was decided upon and construction plans were being made, Ross first wanted the clubhouse on the highest point of land near the site of the current 8th hole, where you could look out over all the trees to see the entire course. But there was not enough room for a large enough clubhouse and all the other space that was needed.

So, the decision was made to place clubhouse near the middle of the property where is today with the caddy shack close to where the snack shop is today.

When Ross was unable to get Mac to leave his caddy master chores at Glen Lakes along with Lupe Trevino and his nephew Lee, he eventually hired Walter Worsham. Better known as “Pops” to one and all, he served as caddy master to oversee the caddies and eventually the carts under both Graham Ross and Ross Collins.

What Pops, a large man of considerable size and height, lacked in formal education, he more than made up for in street smarts and caddy knowledge.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, DAC like most courses was truly a caddie kingdom. Riding carts were sparse and mainly for the very old or infirm and the majority of members at DAC walked and took caddies.

Because of the remoteness of the DAC location in eastern Dallas County, there was no public transportation to the club which meant caddies always had to cover the last 1-2 miles on foot or get picked up by a member or another person in the area on their way to the club.

Caddies lasted until the late 1960s with plenty of stories and warm memories of their work and service for the club.

To gain its highest pro golf event, the 1963 PGA Championship, the club did what so many clubs did in an earlier era, virtually nothing, just indicated they were willing to host the tournament.

So with minimum drama, fancy speeches and extreme politicking, the PGA of America agreed in the summer of ‘61 to bring the first-ever major championship to DAC in two years, July 18-21, 1963. The first PGA Championship in Dallas since Walter Hagen won his fourth straight in 1927, then hid out in the Cedar Crest clubhouse to avoid gamblers he owed money to, was finally assured.

The financial terms were as modest as the tournament was in those days. The PGA of America took the first $40,000 in income along with $50,000 in total revenue. They also collected $80,000 in what was still a fairly new communication medium, television.

In fact, ABC Sports produced one of its first PGA Championship national telecasts from DAC with Chris Schenkel and local golf legend Byron Nelson handling the broadcast duties.

Andrews and other club members spent time shoring up the banks of the natural creeks which run through the property in case heavy rains produced floods at DAC, a worry which turned out to be greatly overstated.

They also planted acres of thick bermuda rough around the large bentgrass greens to penalize anyone who came up short on their approach shots.

“The rough was some of the toughest I had seen in any major championship,” PGA of America executive Joe Black said. “The rough was up to 5-6 inches, common bermuda and matted grass.

“The Salesmanship Club encouraged all the members to act as marshals,” said Don Houseman, who had been in the club for 10 years when the ‘63 tournament rolled around. “I was just a small Indian back then and just wanted to help out. It’s certainly a different deal than the Byron Nelson tournament. We just furnished the labor, the PGA ran the tournament.”

“I marshaled every day,” recalled then-new member Dick Lowe. “I marshaled for Sam Snead who could really be a jerk and Gary Player, who always wanted the crowds moved back, but would always smile and sign autographs for everybody.

“Of course, Arnold Palmer had the biggest galleries, Sam Snead was second, Nicklaus was great with people, but everybody was pulling against him because they wanted Palmer to win.”

For only the fifth time this century, the PGA Championship was held in July, one week after the British Open. It did not go to its traditional August date until a decade later, not that August in Dallas would have been any cooler.

“I was surprised they came to Dallas in July, but it was hot everywhere in the country and the humidity was bad for everybody. I went to the US Open in 1964 in Washington, D.C., where Ken Venturi won, and I almost suffocated there with all the heat and humidity,” Black said.

The National Weather Service reading at Love Field recorded the hottest day of 1963 at 103 degrees during the PGA Championship with an average high temperature of 96 degrees. The weather station at the Naval Air Station between Dallas and Fort Worth recorded the July high temperature of 100 degrees for the fourth and final round.

“One of the biggest problems we had was there was no bottled water then like we have now,” Houseman said. “So there was no real way to carry water around. It would evaporate or get used up in a hurry. People were really desperate for water. You never knew a period that hot in Texas.”

While official Dallas weather statistics record 1980 and 2011 as the two hottest summers in Dallas history, those who were there in 1963 felt it was not far behind.

“We downed plenty of those lemonades they were selling for 25 cents each,” said Buster Brown who attended with his brother Jim. “We’d buy one and sit down and it would already be gone in a few seconds.”

“I was just coming back from the British Open in England where the temperatures had been in the 50s,” Nicklaus remembered. “When I got to DAC, I know I had never been anywhere in my life where it had been that hot. You walked off the airplane in Dallas and the heat just knocked you back.”

Before the tournament began, Nicklaus won the long drive contest at DAC with a whopping pop of 341-yards. When asked recently about his winning drive, Nicklaus boasted that with today’s tech, the drive would’ve likely been much longer.

“I feel like it would’ve been 50 yards longer with today’s equipment.” He said with a wry smile.

The leader after day one of the ’63 PGA was a little known 27-year-old Iowa club pro, Dick Hart.

He used a hole-in-one on the Blue Course’s par-3 16th hole for an opening round 66, just one stroke off the course record. It put him three shots ahead of a tightly bunched field with Nicklaus, Julius Boros, Bob Charles and several others shooting 69.

“The hot weather may have been new to Jack and bothered him, but growing up in Texas like I did, and working in Galveston, I knew what to expect. It was going to be hot at DAC because that’s the way Texas is in the summertime,” said Houston’s Jack Burke, Jr.

The 36-hole cut came at 152, 10-over-par, thanks to a strong wind which fanned up the scores, but did little to abate the heat. Among those going home after 36 holes were Texas golf pro Tod Menefee along with future teacher Jack Fleck and PGA Championship winners Lew Worsham and Lionel Hebert.

Even those still in the hunt took a tumble including Nicklaus who fired a 73, his highest score of the week, and wondered how he was still in the tournament.

“Probably the worst scoring in the history of golf,” he fumed after a midway total of even-par 142 which left him tied for fifth.

But that was all topped by a third-round course-record tying 65 from Australian Bruce Crampton, including five birdies and an eagle in conditions which would have been familiar back home.

“At home we would have been on the beach swimming when the climate is like this,” Crampton said after round three. “We only play golf in the early morning and the late afternoon.”

Abilene, Texas golfer Billy Maxwell shot a third round 69 which left him four shots out of the lead going to the final 18 while Florida golf pro Dave Ragan fired a Saturday 67 and was three shots back.

“It was nothing to walk through the pro shop and see Arnold Palmer at the club machine working on his wedges,” Ewing added. “They had to take care of their own equipment because there was no one else to do it.”

All the extra work failed to pay off as Palmer never broke 70 at DAC and failed to advance in the one major championship he would never win in his career.

While Nicklaus had never led at any time during the 1963 PGA, he had been the steadiest of golfers going to the final 18, using his routine of fairways and greens and not trying anything too fancy or dangerous.

By the back nine at the DAC Blue course, Crampton had faltered and by the 13th hole his lead was gone. A bogey out of the high bermuda rough on 14 had dropped him out of first place for the first time in nearly two days and he never saw that lofty perch again.

Dave Ragan briefly took the lead but gave it right back with a bogey after a wild drive on 17, which left steady Nicklaus to seize command with a 30-foot birdie putt on the 15th hole for his first lead of the week.

He only had three holes left and managed to avoid trouble to hang on for a two-shot victory over Ragan, three better than Finsterwald and Crampton, who struggled with a final round 74, his high score of the week.

Nicklaus won a grand total of $13,000 for his sweaty week at DAC which ended with a final round 68-279 total, five-under-par. He had amassed a total of $75,140 for the year, second only behind Palmer.

At his recent appearance, Nicklaus said he didn’t remember many shots from the championship.

“I don’t remember a shot. Well, maybe just a couple. Remember a five-iron I hit on one and I remember pitching out into the fairway on 18. I do remember I shot the lowest score.”

When it came time for the awards ceremony next to the clubhouse, the huge silver Wanamaker Trophy had been sitting in the North Texas sun most of the afternoon. It was too hot for Nicklaus or anyone else to touch when it came time for the trophy presentation.

Finally, a towel was brought out from the DAC kitchen and Nicklaus and his wife Barbara were able to hoist the trophy in a large photo which still adorns the club’s hallway.

Another big change after the PGA was the retirement of head pro Graham Ross. He had served the club faithfully since its days at Glen Lakes. He had overseen the transition to the East Dallas location and was most responsible for the PGA Championship coming there. Overall, Ross had put in more than 25 years of service to DAC, but he felt it was time to retire due to his age and health.

More importantly for the future success of DAC, he was able to install his former assistant and current Dallas Country Club head pro Ross Collins as his successor.

Collins had spent plenty of time at DAC, having spent nine years as Ross’ assistant, and he knew the club and its members. Now, with previous head pro experience at both Lakewood and DCC, he knew what it took to keep the club moving forward with its PGA Championship prestige.

“Dad was very happy to come back to DAC, especially with all the time he had spent with Graham as his assistant,” said Cary Collins, who worked with his dad at the club along with his brothers Fred and Rip.

“My husband Coy had a chance to see Jack Nicklaus at the ‘63 PGA and when we had a chance to join the club we jumped at the chance,” added Bev Williams.

With the retirement of Graham, the addition of Ross in 1968 took some getting used to, even though he had previously been at the club as an assistant. Ross had flown planes off an aircraft carrier in World War II and still had a formal, military bearing to him.

“He was tough, but fair,” said Cary Collins, his son, who worked at DAC before becoming a head pro.

“I knew all three pros really well,” added Red Johnson.

“Graham Ross was a real whiz, but you didn’t want to fool with him, he wanted a first-class institution. Ross Collins was married, which can be a tough act for a head pro, but his wife brought another voice to the pro shop and he wasn’t as loose as Graham. Dennis (Ewing) was a real hard worker.”

As the club headed into the ‘70s, the allure and momentum of the successful PGA championship had begun to fade, and the club faced money problems once again.

“When I first joined, I think the club was literally broke, so they ran a special deal of $276 for a junior membership and $276 more when you turned 35,” Wells said. “I signed up with a bunch of my friends because we thought that was a great deal. I think the dues were $15 a month and we later raised them to $25.”

Like all successful head pros, Collins always produced assistants who later became successful on their own. Two of the more successful with the longest lasting memories of their mentor was Gilbert Freeman, the current head pro at Lakewood Country Club, and Bob Elliott, the current head pro at the Northwood Club.

“Ross always thought the members should see you sweeping with a broom and he always had us sweeping the front steps by the shop every day,” Freeman recalled. “He said it was good for the members to see us working.”

Since it was first incorporated in 1919 and officially opened in 1925, the downtown Dallas Athletic Club, located at the corners of Elm, St Paul and Pacific streets, had long been the center and the focus of the club’s activities.

But by the beginning of the 1970s, the club’s demographics had shifted, the downtown traffic had shifted, downtown private clubs had definitely shifted, and the original DAC downtown club was facing some tough financial times.

The Olympic sized swimming pool had cracked and never been replaced, the lavish workout facilities were rarely used, and the social dinners were sparse to non-existent.

Plus, the scope of repairs to the downtown building was continuing to increase as the older building needed major and expensive updates while the property taxes continued to rise, further burdening the club’s fragile financial situation.

One of two very different courses of action had to be pursued with two very different outcomes for the club and its future.

But after years of decisions, dissensions and intra-club arguments, the day of decision had finally come in March 1977, and the March 31, 1977 issue of the Dallas Morning News carried the official news; a delight to many, and a dread to others.

At a Tuesday all-club meeting, members of the Dallas Athletic Club officially voted to sell their downtown building to the Dallas Independent School District for the price of $1.5 million. The final vote came out 3 to 1 in favor of the sale, providing the 2/3 majority club leaders needed to officially sell the downtown club.

The DAC quickly cleared out what little club furnishings were still left, and prepared to move everything under one roof for the first time since opening up golf operations in the late 1930s.

“We spent some time at Glen Lakes, even while my Dad and I weren’t golfers, for parties and the like, but we hardly went out to the new club out East,’ said Dees, whose grandfather’s oil strike near Ranger helped provide the land for the original downtown facility. “I was too far away.”

The final blow to the old Dallas Athletic Club came a year later when it disappeared under a ton of well-placed dynamite and backhoes

“We were there for the implosion of the downtown club and it was a huge sight,” said Mattie Lou Smith who was new member at the time with her husband Charlie. “We had not been there before, but it felt like a bit of us was going down as well.”

With the downtown club no more and the PGA Championship a distant memory, the original Plummer DAC courses were beginning to crumble and were in desperate need of work.

So the membership drafted a letter addressed personally to Nicklaus, reminding him about his 1963 PGA Championship win at the DAC Blue course. They asked him if he would consider restoring the course which helped launch his major championship career to its former glory, along with the adjacent Gold Course.

It’s true, the letter detailed, that it would not be a totally new course, but even better, it would be a chance to restore a course and its sister property where Nicklaus had a personal association and had figured so positively in his career.

When the impassioned letter was not immedicably answered, they turned to the next step in their offensive, regular phone calls to Nicklaus’ headquarters. Each time they asked in different forms of urgency that he would at least come back to look at the DAC Blue course, a place he had not visited in 20 years.

“Our manager Scott Sanderson kept calling and calling his office, asking if he would just come look at the course,” Ewing said. “He kept using members’ names that Jack would know and was a real salesman for the club.”

“We kept getting turned down and turned down, but Scott kept calling and asking and finally Jack said he would come down and take a look.”

His first visit came in the winter of 1984 and by that time, Jack’s golf career had begun to cool, and he was becoming more interested in returning to the site of his first PGA Championship.

Nicklaus and his G-Force team had already exchanged some limited financial figures with Lowe and Baker so they would know what to expect. Nicklaus’ fee to do the Blue course would be around $300,000 to $350,000, more than the club had considered spending for just the tees and greens.

When Nicklaus came back for the first time on a chilly winter morning, he was met by a large number of board members, all eager to know what their PGA Champion would propose for the Blue Course and just as importantly, how much it would cost.

“We knew he had a lot of work to do, but I remember it didn’t take Jack long to figure out who was in favor of the project and who was unsure about it,” Wells said. “He rode around with members who were mostly the unsure.”

“I had literally not been back since the 1963 PGA,” Nicklaus said of his 1983 visit in weather almost 60 degrees cooler than his last stop here. “To be honest, I didn’t remember a lot about it. But it’s a lot different when you see the course and don’t have all the tents and people on it and it’s just open ground.”

“Back then, I was just a 23-year-old kid playing my first PGA and I just played the course that was in front of me.”

After the first walkthrough of the two courses, Nicklaus met with the DAC board members in the clubhouse to get their thoughts and see if there was interest from both sides in going forward.

Nicklaus heard plenty of talk from the members, but had received little feedback from Brown, who was known as “the Mayor”, for his many political and civic contacts in Dallas.

“Jack, I figured for the amount of money you want to charge us, I would let you do most of the talking,” Brown replied.

That broke up the room in laughter but confirmed the two parties were still serious about working together.

Nicklaus told the board that there was great cost savings in doing both courses at the same time, essentially giving the club two new courses in 12-18 months.

But struggling to figure out how they were going to pay for one course, doing two at the same time with no place for members to play was simply out of the question.

“The Golden Bear” then made a startling proposal. If the club agreed to do both courses by Nicklaus, one at a time, he would charge the club the same $300,000 for the Gold Course provided they did it within five years, regardless of what he was currently charging at the time.

“There is no question that we would have disappeared and just been down to 18 holes, if Jack had not done something,” Wells said. “Jack literally saved the club with two courses, that’s how big it was.”

Nicklaus would later tell people at DAC and others that they had literally stolen the Gold Course from him, but it turned out to be the key money-saving deal, the second vital long-range decision in the last decade which insured the club’s future.

The grand opening of the new Blue Course took place on May 11, 1986, just weeks after Nicklaus’ historic 6th Masters Championship at Augusta National.

Nicklaus was open about having no qualms about redesigning a course he has such a deep personal connection with.

“I was absolutely delighted to reimagine the course. Despite winning a major here, it was an honor they wanted my insight on how to make this a better club.”

Those that were there for the grand reopening remember it as a high moment in DAC history.

“The greatest day in the history of the club,” head pro Ewing said.

The club membership voted to support the board recommendation and the club was awarded the 1997 U.S. Mid-Amateur. With hard work by the members and the club leaders, the tournament turned out to be hugely successful.

Superintendents Clyde and Kevin Nettles had both the Gold and Blue courses expertly groomed and Ewing had his staff ready to respond to any request or situation.

Based on the reputation of the club and the chance for the top mid-amateurs to see a new course, the Mid-Am at DAC attracted a then-record number of entries for the 1997 National Championship.

In 1999, Clyde, ‘officially,’ retired, but never left the club, serving as a part-time employee and a consultant to his son, Kevin, using his decades of hands-on experience to help his son and the club they both loved and had served so well.

“Not that they needed me, but it’s the best possible thing that could happen,” Clyde said.

“It’s great, it’s awesome. He is the nicest, most gentle person to get along with. I know he only has my best interests at heart, and he wants to make me better,” Kevin added.

“I’m all about having ownership and I feel Clyde and I have ownership. I’m very passionate about this facility. Now I have 33 employees (26 in winter) and a $1.8 million budget. We fish and hunt together and still have a good time. He is the most pleasant, even-tempered person who ever walked on the face of the earth.”

The state amateur, Texas’ most prestigious amateur event also found a home, at Dallas Athletic Club. Newly inducted Texas Golf Hall of Fame member Chip Stewart won on the Blue Course in 1992 and former Baylor University product Ryan Baca captured the state title in 2003, keeping the club in the forefront of top amateur events along the 2019 Texas State Amateur.

Longtime head pro Dennis Ewing had decided to retire after the U.S. Mid-Am at DAC in 1997. He had first worked as an assistant pro and spent 33 years as the head professional, outlasting previous head pros Graham Ross, 25 years, and Ross Collins who served for 11.

He said after four decades he felt it was simply time to go where he could spend time with his wife and family and still play