Golf Science – The Harmon Family Legacy

There is only one family of golf instructors that golf lesson-takers all over the planet, and across all existing golfing generations, might consider the “first family” of golf teachers. And that is, naturally, the Harmon family.

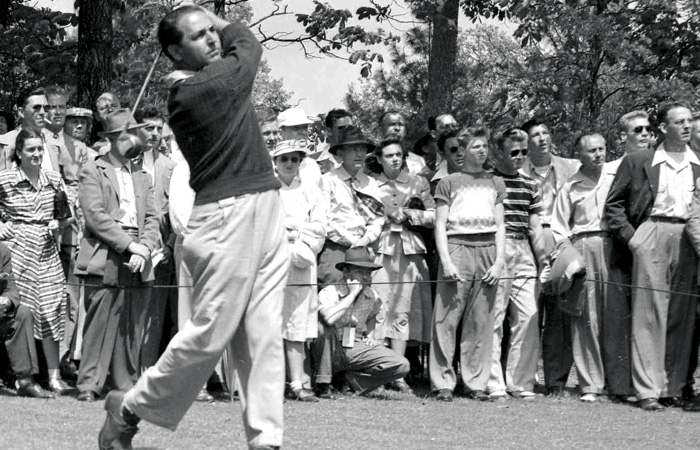

The Patriarch

Eugene Claude Harmon Sr. was a true patriarch for the Harmon family. After having spent much of his boyhood in the Orlando area, he eventually went on to become a golf instructor at Winged Foot Golf Club in New York and, during the winters, at Seminole Golf Club, Florida. He also did stints at Rancho Mirage, California and, eventually, at a golf club in Houston. Despite being a busy club pro with a lot of lessons to give and not enough time to practice, Claude Harmon won the prestigious Masters Tournament in 1948, was a PGA Championship semi-finalist three times, and had a third-place finish at the U.S. Open.

The “Boys”

No wonder that, after their amazing childhood spent around golfers and golf courses, Claude Harmon’s four sons knew, growing up, that they’d like to be golf teachers, too. They were weaned on stories of Harmon’s exhibition game with Gene Sarazen and Walter Hagen when he was a mere 13 years old, exciting tales of famous golfers, and snippets on how best to teach the great game. They all – Claude Jr. (the famous Butch Harmon), Craig, Dick and Bill – did become top teachers, as did grandson Claude Harmon III. Three of the “boys” went on to become Golf Digest Top 50 teachers.

The youngest of the Boys – Bill

Claude Harmon’s youngest son is Bill Harmon, who has played professional golf, been a coach to professional golfers, and caddied on the PGA TOUR, most famously for Jay Haas.

One of Bill’s early memories of Dad’s golfing tales was how, after a great hook around a tree with the ball ending up 3’ from the hole, Winged Foot’s famous pro Craig Wood told Claude it was “the worst golf shot” he’d ever seen. When he later hired Claude to be his assistant at Winged Foot, he changed his grip completely and it took three to four months to settle, eventually leading to Claude’s Masters’ victory. It was, thus, Craig Wood who changed not only Claude’s grip, but gave him the opportunity for a teaching position, which allowed the four boys (one of whom is actually named for Craig Wood) the opportunity to be around some of the best golfers in the country. And it was the grip story that made them all realize that it takes time for a change to settle in.

“We were all pretty good junior players and amateur players, and Butch and I tried the Tour for a while,” Bill Harmon said. “My brothers, Craig and Dick, although nice players, always wanted to be club pros. Butch and I were late bloomers when it came to getting started in our golf profession. I think the thing that helped me the most was that in 1978 I started caddying for Jay Haas.”

The opportunity to learn not only from caddying for a good Tour pro, but also watching top players and teachers over the years, added to Bill’s already strong teaching knowledge that he had gleaned from his father.

Bill says of his golf game in his youth, “I was very, very good and the game came naturally to me, so I didn’t even realize how good I was because I could just do it.” He lost many opportunities, thanks to poor choices in those days, but from the world of recovery he learned that people in that situation get themselves fit enough to be of service to another human being. “You don’t get yourself emotionally and spiritually fit to beat your chest and tell people how great you are, so that training kind of blended in and I found out I was a pretty good teacher,” Bill said. “I also went back to all the fundamentals that our father taught us.”

Observations on the golf swing from a lifetime spent making observations

One very important takeaway from their father, Claude, was something Bill did not always see on the driving ranges of the around 400 PGA TOUR events in which he caddied. Claude always said, “Some people are born very gifted and just have hand-eye coordination, and they have a gift for putting the club on the ball properly. When you’re working with a talented player, be very, very careful what you change, because if they’re on the Tour they probably have a pretty good swing. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have gotten that far.”

Moreover, added Bill, “We were taught to have great respect for talent and that even if we were correct in what we taught them, it might be crisscrossing very intricate, complex wires. So we were taught to be very careful with good players.” Many great players have done the opposite of “typical” but were still very good—Jay Haas, Fred Couples and Kenny Perry – with a lift of the club first, followed by a late turn. They did not have the recommended-at-the-time swing style.

“I think one of the hard things about the golf swing is it’s not straight up and down and it’s not totally around,” Bill Harmon said. “It’s an angle. Something has to put the vertical in it, something has to put the arc in it, and I thought it was interesting that three guys who had played very well into their 60s and even now, were not what I would call one-piece takeaways or early turners – they put the vertical in first.”

Reminiscing about an early lesson he gave, Bill said, “I remember the very first lesson I ever gave was through his (Claude’s) best friend and I gave a terrible lesson, as you can imagine, and when it was over he (Dad) said to me ‘Who was that guy that you were teaching?’ I said, ‘What do you mean? He is your best friend.’” Claude replied to his son that he thought it was a ghostwriter because Bill gave enough information in five minutes to fill a book! Bill was a little upset to be told that because he knew he was right.

Claude patiently explained that it was important not to lose control of a lesson early. A situation should be diagnosed properly, without bombarding a student with information simply to let the student know the teacher knew what he was talking about. “Your job,” Claude had added, “is to improve their quality of strike and help them lower their scores.” Bill got more upset as his Dad explained all that and asked, “Well, how do you know all this?” To which his father smiled and said, “That’s what happened to me when I started to teach!”

Claude then went on to explain what he looked at the first time he gave someone a lesson. The grip, and then how that influences the clubface at the top of the swing. That pretty much told him everything the golfer would have to do on the downswing to hit a good shot.

Bill, speaking of that first exhortation from his dad said, “Now you have to remember he learned all this stuff in the ‘40s, and they didn’t have measuring devices or video and YouTube and all this stuff. So he had to figure some of this stuff out himself, and that was a great a lesson for me early on. We talked about the clubface a lot. This was before measuring things and knowing that the ball starts at 75 percent clubface and 25 percent path. He (Dad) used to say ‘You know, the ball goes where the clubface tells it to go.’” The father gave all his sons a wonderful foundation and always wanted them to try to figure out cause and effect.

One day Bill said, “Dad what do I have to do to be a good teacher?” To which he received a very interesting response, which he feels might not be popular today. “You have to acquire lots of knowledge, you have to have great communication skills (because back then we didn’t have videos and stuff to distract us), you have to know how to diagnose the problem, then come up with one thing to change five, not five things to change one. And you have to have the type of personality that someone actually wants to spend an hour with. If you can do those four things, I think your lesson book will be filled.”

Does Bill, at his teaching location at Toscana Country Club in the Coachella Valley region of California, now teach differently from the basics his father taught him? “I like taking lessons from other people and learning from other people, but at the end of the day, the clubface is the only thing that gets the ball.”

In fact, one more inspiring piece of advice that he got from his father and still uses is that the game has four parts: 1. Can the student hit a golf ball? 2. What’s the short game like? 3. How does the student manage him/herself? 4. How does the person manage the golf course? This useful knowledge was learned by Claude after playing daily for a month every year with Ben Hogan, when each of them had to put $10 into a hat each time they missed a fairway or a green. With those stakes, a person had to learn how to manage the course!

Now Bill teaches the game and those four parts by telling his students to, “Become a little better ball-striker, a little better at short game, a little better at managing yourself and a little better at golf course management. Then it will be pretty easy to reduce your handicap 25 percent, and you don’t have to get remarkably better, just a little bit.”

“I look at the grip a lot,” Bill said. “Grip influences clubface dramatically, and clubface influences the path of the club dramatically. If I had to choose for the recreational golfer, I’d much prefer a strong grip than a weak grip, and I would much prefer a slightly shut clubface. I try to explain that from the start of the downswing to impact takes a quarter of a second, and if you have a bad grip and a bad setup and a bad back swing, you just don’t have time to fix it.”

Another useful idea from Bill based on his experience is to take golfers who have the fear factor out onto the golf course, then have them take two or three rehearsal swings and have them hold their finish for one or two seconds, before having them go up to the ball and go to that finish after making the shot. He has had a lot of success with this concept. He believes it helps a person to give up control of the result while out playing on the golf course.

During a typical lesson, Bill might not say a word for 10 minutes as he watches his student hit shots, because he does not want to fill the golfer’s mind with rubbish – a lesson well-learned from his father’s theory of how best to teach. “I’m always looking for the one thing that will improve all the other things, and then I like to have about 10 different ways of explaining it and seeing what actually helps them change.”

Finally, he will map out a long-term plan and tell the student to see what, together, they can chip away at. “I like the long-term approach. I need them to understand that not every lesson is going to be great,” Bill said.

In fact, he will ask his business-executive clients, “What’s your current handicap? What’s your lowest? How long have you been playing?” If they were to have a response like 18, 16 and 30, he’d tell them that in their business they might fire somebody who had performed to a level of 16 and then had an 18 level of performance 30 years later. So, with their golf, they should just take the time and patience to achieve their desired results.

A lesson from the youngest of the famed Harmon brothers then is based on his belief that “You have an opportunity to make another human being happy, and I think that’s the real reason that I teach. Not the handicap, not all that other stuff, but just to see the look on their face when they get it.”