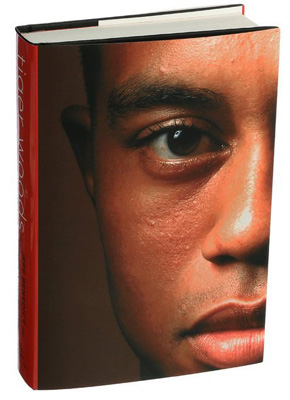

A New Book On Tiger Woods Reveals Much About The Complex Life Of A Superstar

Tiger Woods’ life has been chronicled countless times. One that’s a complex cocktail of fame, fortune and superhuman skills offset with a weird upbringing, reckless choices, an overbearing father in addition to dealing with the endless pressure of being the best of his generation–if not the entire history of his sport.

The New York Times released a review of the book “Tiger Woods” prior to it being available to the public. From the review, it appears to be a fascinating read by two writers (Jeff Benedict and Armen Keteyian) known for their extensive responsible research and homework.

What’s also evident is just when Woods had seemingly turned the corner on maturity, friendliness and being comfortable in his skin, the book’s timing will undoubtedly open up a new session of scrutiny from a fervent fan/enemy base that can’t get enough of El Tigre. And that’s unfortunate as Woods appears serious and genuine about changing his persona.

I found it exhilarating, depressing, tawdry and moving in almost equal measure. It’s a big American story that rolls across barbered lawns and then leaves you stranded in some all-night Sam’s Club of the soul. It reminded me of a line from Martin Amis’s new book of essays: “How drunk was Scott Fitzgerald when he said there were no second acts in American lives?”

At the time, Elin didn’t know the half of it. Woods’s paramours (strippers, waitresses, neighbors) began popping up from behind every swizzle stick. The scandal was on the cover of The New York Post for 21 consecutive days; each issue was so sleazy you wanted to pick it up with tongs. (The Sept. 11 attacks, by contrast, managed only 20 straight covers.) This was a purge of schadenfreude. Many were delighted to see this ostensible paragon of virtue take a fall.

In “Tiger Woods” they take special aim at Woods’s parents, especially Earl Woods, Tiger’s father. They raised a champion. They also raised a narcissistic loner who lacked basic decency. “Even the most basic human civilities — a simple hello or thank you — routinely went missing from his vocabulary. A nod was too much to expect.”

This book is littered with the bodies of those Woods cut out of his life without a thank you or goodbye — girlfriends, coaches, agents, caddies. If you stripped most of the golf out of this book, you might sometimes think you are reading the biography of a sociopath, a nonmurderous Tom Ripley or Patrick Bateman or Svidrigailov from “Crime and Punishment.”

Who is Tiger Woods? The authors don’t get to the bottom of that question, but does anyone really expect that they could? Woods himself doesn’t appear to have a clue.

Whom the gods will destroy, Cyril Connelly said, they first call promising. This intense book gives us Woods’s almost mythical rise and fall. It has torque and velocity, even when all of Woods’s shots, on the course and off it, begin heading for the weeds.

I for one will be in line to pick one up.