Golf Science – The Golf Professor’s Evaluation

Golfers of all skill levels – beginner to Tour player – often struggle with directional misses, loss of distance, and even injury. Despite trying various adjustments – from grip changes and takeaway modifications – to the latest “power” moves or “miracle” cures, they often find that their results remain inconsistent, and the fixes are frequently short-lived or even harmful.

Like many golfers who have experienced this cycle of frustration, you might resign yourself to inconsistency, thinking, “That’s just golf.” Even leading biomechanists in the field concur with the perception of the golf swing’s difficulty. Dr. Ralph Mann has described it as “enormously complex,” and Dr. Steven Nesbit considers it “one of the most difficult biomechanical motions in sport.’

Why IS the Swing So Complex?

Mainly because golfers are required to rotate their shoulders around a forward-flexed spine. The result is that the lead side (left for right-handed golfer) lowers and the trail side rises, because rotation around a forward-facing chest is always accompanied by side bend.

This steepens the arms’ and hands’ plane at the top. Even when golfers attempt to swing “inside” or “deep,” as do Rory McIlroy and Bryson DeChambeau, especially with their drivers, the arms remain steeper than they could because of the side bend of the torso, along with the changes in hip and knee levels.

To then have to synchronize the body and the arms in the downswing is what causes all swing issues.

Why is Synchronization Such a Problem?

While the pelvis and chest/shoulders rotate on a fairly horizontal plane, the arms tend to rotate on a more vertical plane. How and when should a golfer match up these disparate movements?

Keep in mind that the arms and hands are lighter and easier to move and receive significantly more neural signals from the brain to facilitate their muscle activation. Conversely, the torso is a heavy and relatively slow-moving segment with limited nerve supply from the brain.

Additionally, our brains are wired for goal-directed movement, a trait so ancient that it allowed our hunter-gatherer ancestors to easily reach for fruit from trees or bring food to the mouth. This inherent programming favors moving the hands straight down toward the ball – an efficient and intuitive action that utilizes gravity as a movement strategy rather than excessive muscle force. In fact, it is this neurological and biomechanical predisposition that contributes to the prevalence of over-the-top downswing movements.

So, the problem lies in having to somehow slow down the arms and force them to hang back (shallow?), so that the pelvis can catch up.

But the swing doesn’t have to be complex. There are scientific, researched ways to simplify your swing for best-possible results.

A New Way to Understand Your Swing

As a golf professor and movement-science specialist (including PhD-level coursework in biomechanics, anatomy, neuroanatomy and motor control), I’ve focused on simplifying the golf swing by analyzing how the body can achieve optimal movement.

The result is my unique swing evaluation, powered by the XView app created by IdeasLab, which enables you to quickly pinpoint your source of swing issues, such as distance loss, directional misses, and even injury. The evaluation is then followed by a simple, scientific solution.

Try the Evaluation in Five Easy Steps

Get X View Golf: Search for XView Golf in the App Store, download it, and enter the code “kiran25” for a free seven-day trial.

Record a video: Record a slow-motion swing at 240 fps from a down-the-line view, keeping the entire club visible at all times. Import it into XView Golf.

Trim the video: For a faster analysis, use the slider on the XView screen to trim your video, keeping just enough swing from the start of the backswing to the finish.

Draw two lines: Use the line feature on the right side of your screen. Draw a line from your ball to your hands at the top of your backswing (the Top Line). Draw another line from the ball to your hands at impact (Impact Line).

Track your hand path: Click on “Path” in the top bar on your screen, then click on the fourth-from-left icon (only) at the bottom of the screen. That will give you a downswing Hand Path.

What is the Top Line?

It is defined in the vertical plane from a down-the-line perspective – an indication of how high your hands are relative to the ball-ground plane.

What is the Impact Line?

It is an indication of how steep your hands are at impact. If the Top and Impact Lines are a close match, the hand-steepness relative to the ground has not changed much. This can be good or bad.

Good if the hand steepness is not excessive to start with.

Bad if top-of-backswing hand steepness is excessive and the golfer cannot adequately reroute the entire platform (head, scapulae, shoulders, pelvis and legs) to deliver the arms, hands and club to the ball from an inside path. It could be said that the hands are steeper than they need to be whenever the lead side lowers and the trail side rises during the backswing.

What is the Downswing Hand Path?

The Hand Path tracks the movement of the mid-hands during your downswing and helps you to easily assess what your hands do to get from the top to impact.

A fairly straight-line path indicates that the hands are dropping vertically. Golfers will always have a straight drop-down of the hands from the top or shortly thereafter, unless they have enough skill and practice to attempt a sophisticated body motion in conjunction. If you analyze your own hand path during the back- and down-swings, you’ll observe that your downswing path is much steeper. This further supports the idea that the hands always try to drop downward and forward in the downswing.

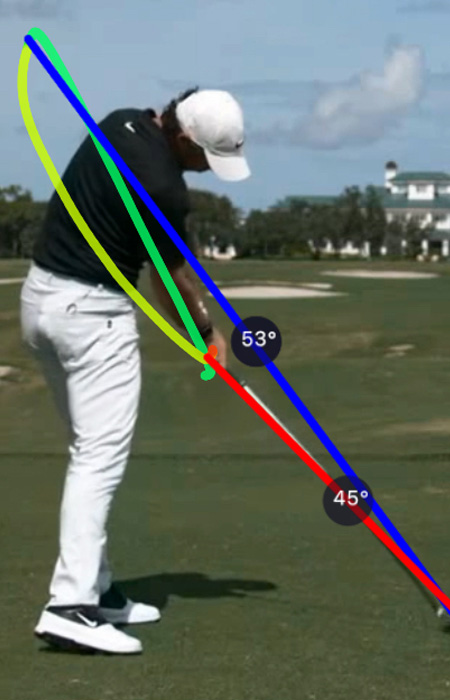

A considerably curved hand path, as seen in the swings of Rory McIlroy and Bryson DeChambeau, for instance, reveals a substantial and complex rerouting of the body to maintain the hands in a “shallower” position. This rerouting appears visually to shallow the shaft, while it can increase downswing complexity and cause timing difficulties.

Why Shallowing is Not Easy or, for Many, Impossible

Shallowing the club, which involves dropping the torso and trail-side scapula backward, may facilitate a more inside path to the ball, but is a complex maneuver that’s difficult to execute consistently. Especially because it’s a natural downswing hand path

Consider the intricate coordination required: The motor control system must orchestrate the lowering of the elevated trail side, the lifting and rotating of the lowered lead side, the descent of the arms, hands and club with straightening of the wrists, and the synchronization of the body and arms in a precise ground-up sequence. Executing this change of direction from backswing to downswing is a demanding motion.

Furthermore, given the downswing’s rapid execution (occurring in 300 milliseconds or less), a slight mistiming between torso movements and hand delivery can result in inconsistent strikes. This is true even for highly skilled golfers like Rory McIlroy and Bryson DeChambeau, especially when they are anxious, stressed or fatigued.

Interestingly, both McIlroy and DeChambeau position their hands quite “deep” in their backswings (further back from the target line), with their drivers. Even when the hands are “deep,” as long as body and leg levels have to change during the downswing, the hand path becomes complex.

From the top, DeChambeau (even with his driver – not shown here) reroutes his hands (yellow curve) probably by keeping his thorax facing away from target at the start of his downswing (looping yellow curve). However, his hands soon return to a rather steep downswing path (yellow line overlaps green line). Hence, his occasional inconsistencies.

In contrast, McIlroy manipulates his downswing hand path (yellow curve), so that it is substantially behind and shallower than his backswing path. This is a rare and very intricate motion. David Duval of the PGA TOUR Champions also has a similar shallower downswing hand path and has said, when interviewed (see April issue), that what he struggles with most is his transition.

How do TOUR Champions players cope? The conventional swing is challenging for older golfers, due to the difficulty of executing rapid pelvic rotation, along with coordinating all other movements. The body is being asked to do too much, in too little time, and with too many moving segments. Even when they are able to rotate the pelvis, the required pelvis-thorax separation cannot occur and everything tends to move down and forward together.

A case in point is that of Padraig Harrington. He fears a leftward miss and says that he attempts to counteract that through a “constant” release rather than a “late” one (see the April issue for the exact quote). Regardless of his intent, he demonstrates an almost identical Impact Line (red) to his Top Line (blue), indicating a steep hands drop-down, despite at first attempting to keep the hands back (yellow line). The resulting upper body rotation to an open position at impact causes his arms and clubface to move left of the target. That, in turn, leads to his dreaded pulled and hooked shots, when he cannot compensate adequately and in time.

Notah Begay III also exhibits an extremely steep hand path, with his Top Line and Impact Line nearly identical (the precise steepness is unclear due to a poor camera angle). During a March ’25 Galleri Classic interview (see the April issue for details), he expressed frustration with blocked shots.

He says that his hands get stuck behind as he rotates his pelvis. The cause of his difficulty stems from attempting a complex pelvic rotation in the first place, because it forces the highly coupled thorax to move downward and forward, too. As every part of his torso is now “open” to target, naturally his trail arm is stuck behind him, but that is merely incidental to his problem. What matters is that his hands descend steeply and inevitably, creating inconsistency of face angle at impact.

The ball flight ensuing from a steep hand drop-down can be inconsistent. As Kirk Triplett famously said at the Hoag Classic TOUR Champions event (see the April issue for details), you’re often forced to “take what your clubface gives you.”

Imagine if you could design your setup and swing so that the clubface gave you exactly what you wanted – every time? Keeping in mind that a steep hands drop-down is practically inevitable, why fight it?

What’s a Viable Solution?

The key is to design your address position and backswing correctly, eliminating the need for any too-late mid-downswing corrections in the remaining milliseconds to impact.

Begin by setting up with your hands slightly higher at address to encourage the arms and shaft to move to the top in a straight line with no intentional wrist bend.

Next, make your backswing while keeping your head and trail-side waist in place (no lifting or shifting), so that your shoulders can be level at the top. This will produce a less steep Top Line for any given club, compared to a typical swing. There will, as a result, be greater ball-striking consistency and reduced lower back injury risk.

Once you’ve mastered this initial setup and backswing, the next step is to push your lead arm and club shaft “in” toward your right heel, creating a more “closed” position. This action will result in your arms pushing your trail scapula and thorax back away from the target line, without any intentional rotation.

That, in turn, will stretch key swing muscles – pectorals, latissimus dorsi, obliques – allowing them to contract powerfully during the downswing for increased power at impact. The inside backswing arm movement naturally encourages a more inside path for the hands and club on the way down.

The downswing is made, as it should be, with no conscious thought. It unconsciously incorporates your entire wish-list of requirements. There is a slight, toward-target weight shift, ample vertical force, and any required rotation. This approach allows you to harness your body’s inherent elasticity for clubhead speed and distance without any unnatural, forced movements or risk of injury. It is far more effective than relying on exaggerated hip turn, wrist lag, or excessive “ground force.”

Effortless Position and Power

Note the relatively shallow Top Line for an iron (left) and wood (right), followed by an almost straight hand path and well-matched Impact Line.

This indicates limited rerouting in the downswing. Plenty of club speed and straight direction are generated as a result of an adequately inside path of the arms and club in the backswing.

A Holistic Approach to the Golf Swing

This is more than a swing “fix.” The prescribed movements are the result of 32 years of research, much of which has been published and rigorously refined. This approach is a reverse-engineering of the requirements of optimal impact and represents a complete rethinking of joint movement, grounded in the body’s natural mechanics. It is the 21st-century solution to great golf.

The recommended movements are designed to maximize distance and directional control, while minimizing inconsistency and injury. The arms drop down from the top, with late and forceful big-muscle action for greater club speed. When a swing aligns with the body’s design constraints, it transforms from constant trial-and-error to a repeatable, fluid and powerful movement.

If you are an elite golfer wishing to learn this simple yet powerful swing and receive personalized guidance tailored to your learning style, contact me at www.YourGolfGuru.com. Partial implementation of this method is discouraged, as it may simply substitute one set of inconsistencies for another.